“The envy motif is deeply rooted in the economic policy discourse in Europe”

In times of weak growth, it is easier to stir up envy

“No more billions for the greedy Greeks!” Campaigns by newspapers such as Bild-Zeitung and statements by leading European economic policymakers have stirred up envy in different contexts. I did an interview with the Austrian newspaper “Die Presse” on some major envy debates in European economic policy making during the last two decades. Below, you find an English version.

Interviewer: “How can debates on justice be distinguished from debates on envy, for example when it comes to the distribution of resources within states or between states, e.g. within the EU?”

Debates on justice revolve around normative principles: Equality, fairness, meritocracy, etc. What distribution is fair? These are debates that are open to nuanced arguments.

Envy debates, on the other hand, deliberately seek to activate base instincts in politics and society. They are highly emotionally charged; the emotion is intended to nip rational thought about nuances, pros and cons in the bud. Envy debates are particularly effective when they fuel personal or collective dissatisfaction that others are taking it easy and lying on their lazy backs, which is only possible thanks to the honest and hard work of the exploited core group.

This can then be transferred to disputes between EU states, for example during the euro crisis: politicians in northern countries repeatedly claimed that southern Europeans had been having a good time at the expense of taxpayers in northern Europe for a long time; and now these brazen people also want “us” to pay for the crisis caused by their excesses! The stoked emotions are intended to stifle any consideration of the systemic causes of the crisis in a complex system in which the northern countries also made a significant contribution to the emergence of macroeconomic imbalances, which later exacerbated the crisis.

Interviewer: “Would you say that periods of weak economic growth (and increased uncertainty) are a breeding ground for envy debates?”

There is recent research that suggests that in times of weak growth, “zero-sum thinking” increases: that is, more people hold the worldview that the gains of some are always the losses of others, based on the assumption that societal output is limited; effort and exchange cannot create value, only redistribute it.

When “zero-sum thinking” takes hold in times of weak growth, higher unemployment and rampant fears about the future, it is easier to stir up further envy. This makes it easier to score points by claiming that politicians must expel large numbers of migrants and stop further immigration, as this is the only way for the native population to win. And it is also easier to succeed with the argument that we need to seal ourselves off more from neighboring countries, as this is the only way to gain an economic advantage at home.

Interviewer: “Have there been any major European envy debates in recent years/decades?”

There were major economic policy envy debates that lasted for many years, particularly during the euro crisis in the 2010s and during the Covid crisis (2020-2021). “I can't spend all my money on liqueurs and women and then go and ask for your support”, said the then Eurogroup leader Jeroen Dijsselbloem (the Dutch Finance Minister) in the context of the euro crisis in the direction of the crisis-ridden countries in southern Europe.

German Finance Minister Wolfgang Schäuble had already called for austerity policies in southern Europe at the height of the euro crisis, claiming that “excessive deficits and debt levels” had caused the crisis: “You can't cure an alcoholic by giving him alcohol.” Major German-language newspapers enthusiastically reported such political statements and wove them into their envy-inducing coverage of the crisis in southern European countries. The Bild newspaper, for example, ran a one-sided campaign against Greece in particular for years: “Why are we paying the Greeks their luxury pensions?”, “Why don't you sell your islands, you bankrupt Greeks... and the Acropolis too” - these were among the headlines in those years. The aim was to create a mood against Greece among German readers and thereby increase the pressure on German politicians to align crisis policy with nationalist considerations.

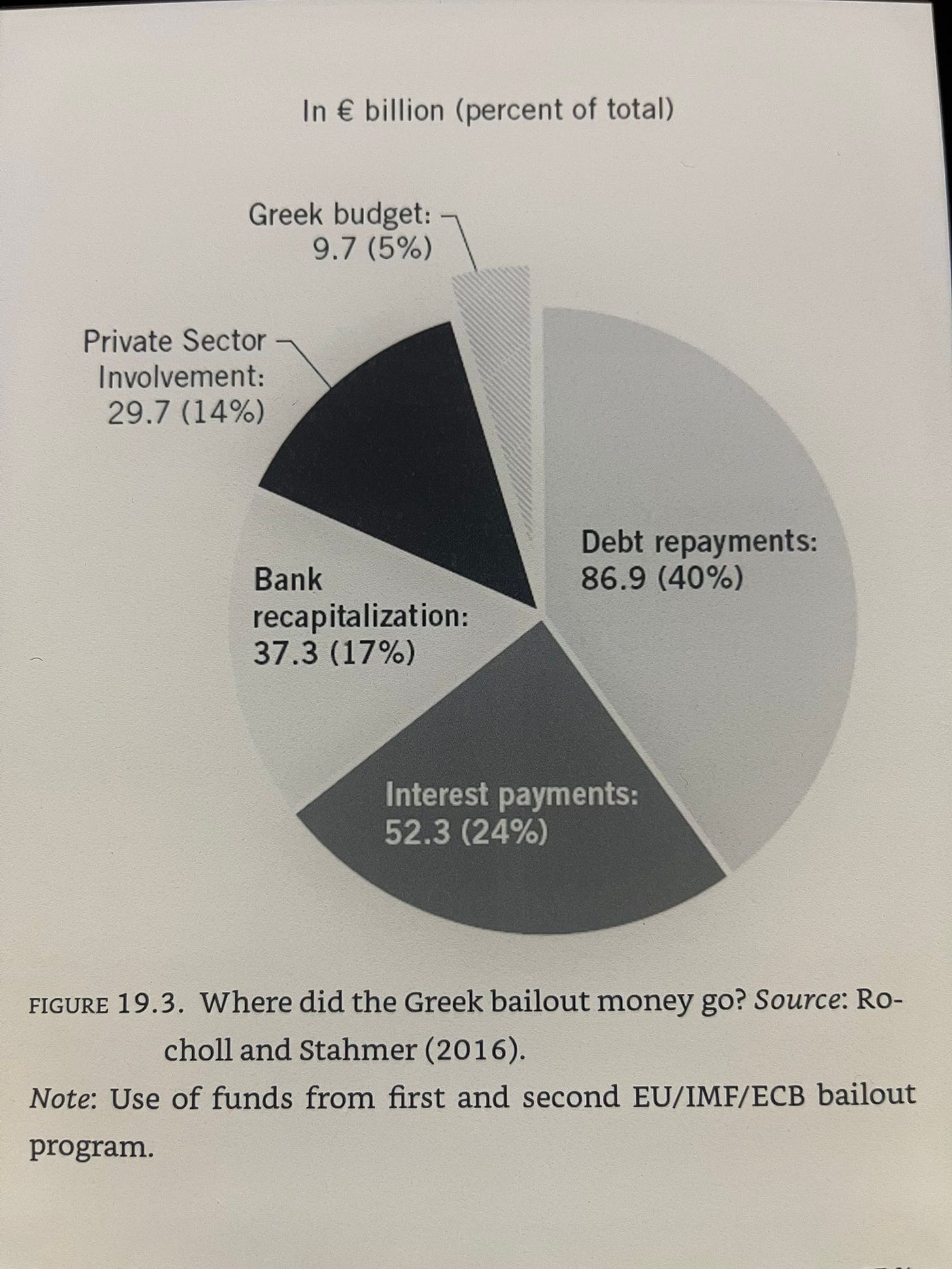

The fact that the first “aid packages” for Greece were primarily intended to minimize the losses of German and French banks, which held a large proportion of Greek government bonds, was not worthy of headlines - after all, this was not a way to create a mood against the Greeks.

During the Covid crisis, especially in the first few months, leading northern European politicians focused on Italy and Spain, which were particularly hard hit by the waves of infection. If the governments in these countries failed to prepare their healthcare systems for such a crisis, why should “we” in Northern Europe now pay for the “failures”? Why should there be European subsidies (non-repayable loans) for these countries if the money is only being “squandered” there anyway, as has been seen time and again in the past? Several member states - including Austria - entered the negotiations surrounding the Covid recovery fund with nationalistic, envy-inducing undertones; leading politicians used base instincts to create a supposedly better negotiating position for themselves.

Interviewer: “Is envy a factor or obstacle in the integration of European fiscal policy, for example?”

During the aforementioned crises, the stirring up of envy - along the lines of: “We” are certainly not paying for your fiscal profligacy - was most pronounced. But in slightly adapted forms, this keeps cropping up in debates on European fiscal policy. This envy motif is now so well anchored in the discursive substructure that it can also be activated quite quickly.

Thanks for posting this. We developed these self-defeating narratives (with symmetrically misleading ones in southern countries) entirely on our own, well before Musk’s takeover of Twitter and without any foreign influence. On the positive side, the response to the COVID-19 pandemic outbreak showed that a different narrative is possible, although the path is way more narrow than it should be (on purely rational grounds).

A great interview Philipp! Weaponisation of envy as a political narrative to suppress discussion about systemic/structural failings is endemic to the EU but also the conversation around loans/debt-restructuring more broadly, serving the us/them dichotomy. Similar lines of argument are found around IMF interventions and the failure to look at the historical facts which contribute to the current state of affairs. Curious to know if you’ve read Robert Shiller’s Narrative Economics which speaks to this in a general sense, found it a great read myself.