Financial globalisation has increased income inequality

Globalisation is an important driver of income inequality within countries, but mostly via financial rather than trade channels.

· Since the 1980s, income inequality has been rising within many advanced and developing countries.

· Globalisation is often considered to play an important role in explaining rising inequality.

· My recent meta-analysis of the relevant econometric literature shows that economic globalisation, on average, has a small-to-medium-sized effect of increasing income inequality - which, however, can be explained less by trade globalisation than by financial globalisation.

Direction and magnitude of the effect of globalisation on inequality are controversial

Several explanations exist to explain the increasing income inequality within nation states since the 1980s. An inequality indicator that clearly points towards rising within country inequality across Europe and in the US is the share of the incomes of the top-10% in pre-tax national income.

One explanation for rising inequality relates to economic globalisation: in recent decades, questions of how increasing market integration in the areas of international trade and finance has affected income inequality around the world have been at the centre of social science controversy. Academic scholarship has contributed to a rapidly growing body of literature.

Source: World Inequality Database.

Despite considerable research efforts, different and partly contradictory results are being reported in the literature regarding the direction and magnitude of the effect of globalisation on inequality. At the theoretical level, the most prominent theory is the so-called Stolper-Samuelson theorem, which states that increasing international trade integration reduces income inequality within developing countries but increases inequality within advanced countries. Other theories concern the effect of financial openness on distributional aspects. Here, it is often suggested that the opening of financial markets should be accompanied by an improvement in financing opportunities - with ambivalent distributional effects - and a tendency to increasing inequality and vulnerability to crises.

The empirical literature concerning the effect of trade globalisation on income inequality is quite voluminous. There is both support for the Stolper-Samuelson theorem and refutation. Increasingly, however, aspects of globalisation that do not revolve around the trade in goods and services are also coming into focus. The increasing international integration of financial markets and the growing number of financial crises have led to numerous studies on the financial dimension of globalisation in recent decades - but with equally contradictory conclusions.

Another line of research deals with the question of whether the influence of globalisation is not so important because domestic political, institutional or other factors (such as technology, education or macroeconomic variables) are much more important for the development of inequality, even if these factors are not entirely independent.

Meta-analysis of the globalisation-inequality nexus

In view of the large number of results reported in the empirical literature, it is advisable to evaluate them systematically and, if possible, to derive stylised facts from them instead of selectively picking out individual results. A so-called meta-analysis can provide useful services here. This involves collecting the results and characteristics of a large number of studies on the topic and systematically evaluating them using statistical methods.

What do existing studies tell us about the effect of globalisation on income inequality? And what factors contribute to explaining the differences in reported findings on the relationship between globalisation and inequality? To answer these questions, I have conducted a quantitative survey of 123 relevant English-language econometric studies published in peer-reviewed academic journal articles by analysing the effects of economic globalisation on income inequality reported in these studies. The paper has recently been published in the journal “World Economy”.

First of all, it must be clarified how "economic globalisation" can be defined and measured. Brady et al. propose that economic globalisation should be understood as "the intensification of international economic exchange and the label for the contemporary era of international economic integration. Thus, [economic] globalisation involves the current economic environment shaping welfare states and the heightening of concrete economic exchanges between countries ". Hence, three dimensions of international market integration are captured: Trade globalisation, financial globalisation and overall economic globalisation, whereby measures of the latter combine the dimensions of trade and financial globalisation.

By far the most important indicator of trade globalisation is trade openness, which is typically measured as the sum of imports and exports as a percentage of GDP, although there are many other indicators of trade openness. In the dimension of financial globalisation, researchers have used measures such as foreign direct investment and indices of capital account liberalisation. In addition, the Globalisation Index of the KOF Swiss Economic Institute has become probably the most widely used overall globalisation index.

Adverse distributional effects of globalisation

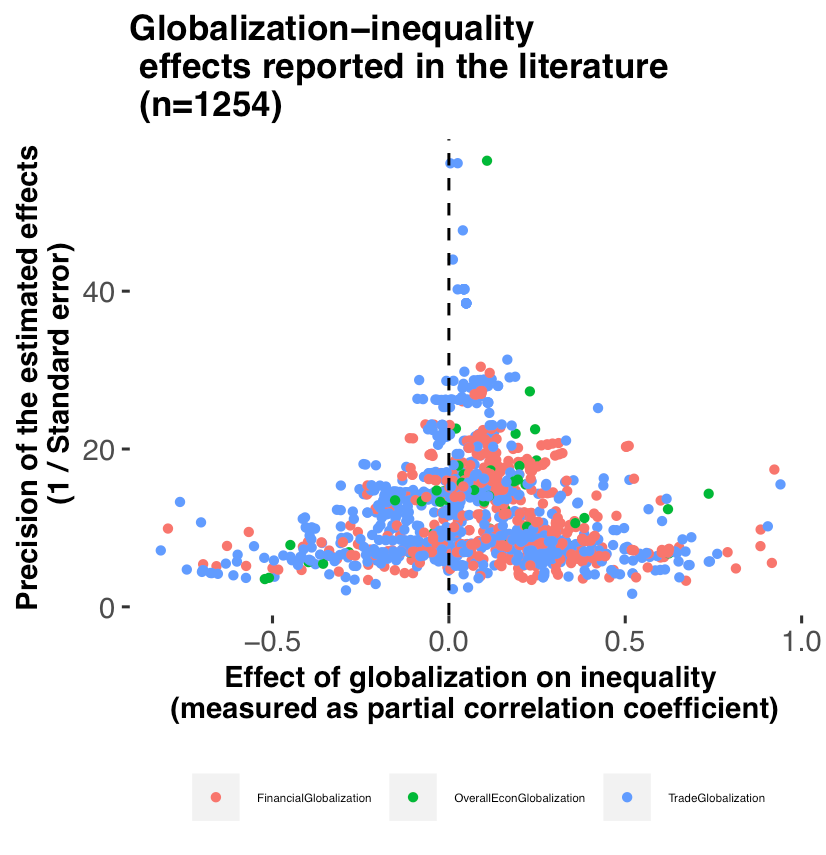

If one evaluates the more than 1,000 individual results from the 123 published studies that I collected, the first thing that becomes apparent is that they are relatively widely scattered. There are results that indicate an equalizing distributional effect due to globalisation as well as those that find an effect in the direction of stronger income concentration at the top.

Source: Heimberger (2020).

Second, it can be seen that inequality-increasing effect sizes predominate - especially for the subgroup of financial globalisation. Surprisingly, however, there are no significant differences between advanced countries and developing countries.

Third, my meta-analysis shows that variables that proxy for education and technology influence the distributional effects of globalisation reported in the econometric literature; education and technology themselves are part of the explanation for changes in income inequality, and they seem to moderate the effect of globalisation.

Conclusions

The meta-analysis and meta-regression results presented in my paper suggest that globalisation has, on average, a small-to-medium-sized effect of increasing income inequality. Financial globalisation has influenced income inequality to a larger extent than trade globalisation. Obviously, globalization is not the only factor to impact on income inequality, as welfare state policies and domestic institutional developments have likely also played an important role. But my meta-study shows that the negative income distribution effects of (financial) globalisation should not be neglected.

However, this quantitative analysis cannot clarify further questions. One important area for future research concerns whether globalisation has a transformative impact on other policy-relevant phenomena - in particular on redistribution by the state and on growing right-wing populism. For example, there is evidence that rising import competition with China in the context of globalization has caused negative local employment effects in the US, and congressional districts exposed to larger increases in globalization-induced import competition disproportionately removed moderate representatives from office in the 2000s: where jobs are squeezed by globalization-induced pressures, voters may tend to favour more extreme political candidates. More research is to be done on the link between the (dis)contents of globalization and electoral outcomes in Europe.

A second essential area for an extended analysis concerns the time- and location-specific forms of globalisation: past efforts to enhance trade globalisation by reducing tariffs are different from trade globalisation today, where bilateral and multilateral attempts are being used to harmonise standards across countries or to enforce special rights for big multinational companies. Further and broader studies are therefore indispensable - especially with regard to the question of how economic policy-makers should try to shape globalisation in the post-COVID-19 future in order to achieve the desired policy effects.

Note: This article was slightly adapted based on an article that was previously published on the website of the Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies (wiiw).