This article was first published in Italian in the magazine “La rivista il Mulino”.

Italy - heavily in debt, unwilling to reform and thereby pushing all of Europe towards the abyss! In the run-up to Italy’s general election in September, countless articles were again published in international media that struck such a tone. Indeed, the standard narrative on Italy in Germany, Austria and other countries is still that reckless fiscal spending and a lack of “structural reforms” based on European best-practices are major sources of Italy’s economic problems.

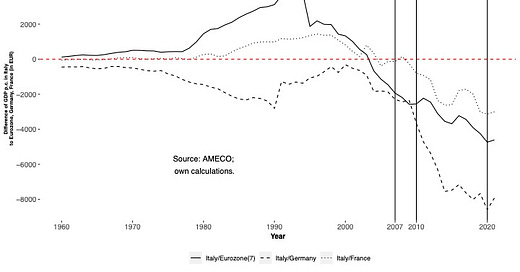

Italy indeed faces major problems. Over the last decades, labour productivity issues and a lacklustre industrial performance have culminated in substantial losses in relative living standards. Up to the late 1990s, Italy’s income per capita was still higher than in France and other Eurozone countries and only slightly lower than in Germany. However, a large gap has opened up over the last two decades, so that Italy’s GDP per capita in 2021 was about €8000 lower than in Germany and roughly €3000 lower than in France.

Unfortunately, the simplistic standard narrative on how Italy ended up with its long decline typically remains unchallenged: “Italians have been living above their means; they finally need to adjust!” While this position dominates public discourse on European issues, it is high time to take a data-based look at Italy and, in doing so, also dispel some myths that unfortunately continue to be spread regularly by international media, which promotes a lop-sided economic policy debate.

Italy has not been living beyond its means

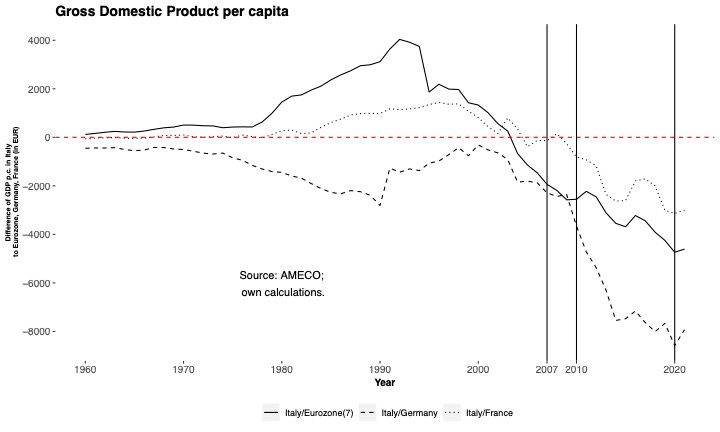

From a macroeconomic perspective, a country can live beyond its means if it imports significantly more goods and services than it exports over a longer period of time, which goes hand in hand with rising foreign debt. If, on the other hand, roughly the same amount is exported as is imported, it makes little sense to speak of "living beyond one's means", because production and consumption match. And in Italy it is even the case that since 2012 the country has recorded higher exports of goods and services than imports. The country consumes less than it produces. If anything, Italians are not living above their means, but below their means.

Public debt is high because of the legacy of the 1980s and recent crises

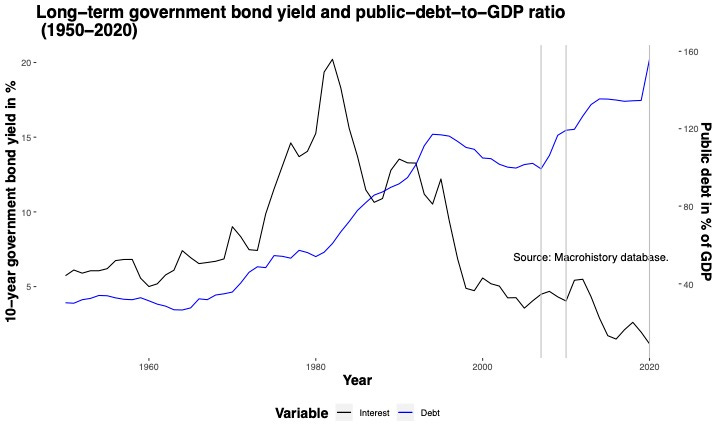

Private sector debt in Italy is low in comparison with other OECD countries. Overall debt is certainly not a bigger issue in Italy than in other European countries. But Italy’s public-debt-to-GDP ratio at around 150% of economic output is the second-highest in the euro area just behind Greece.

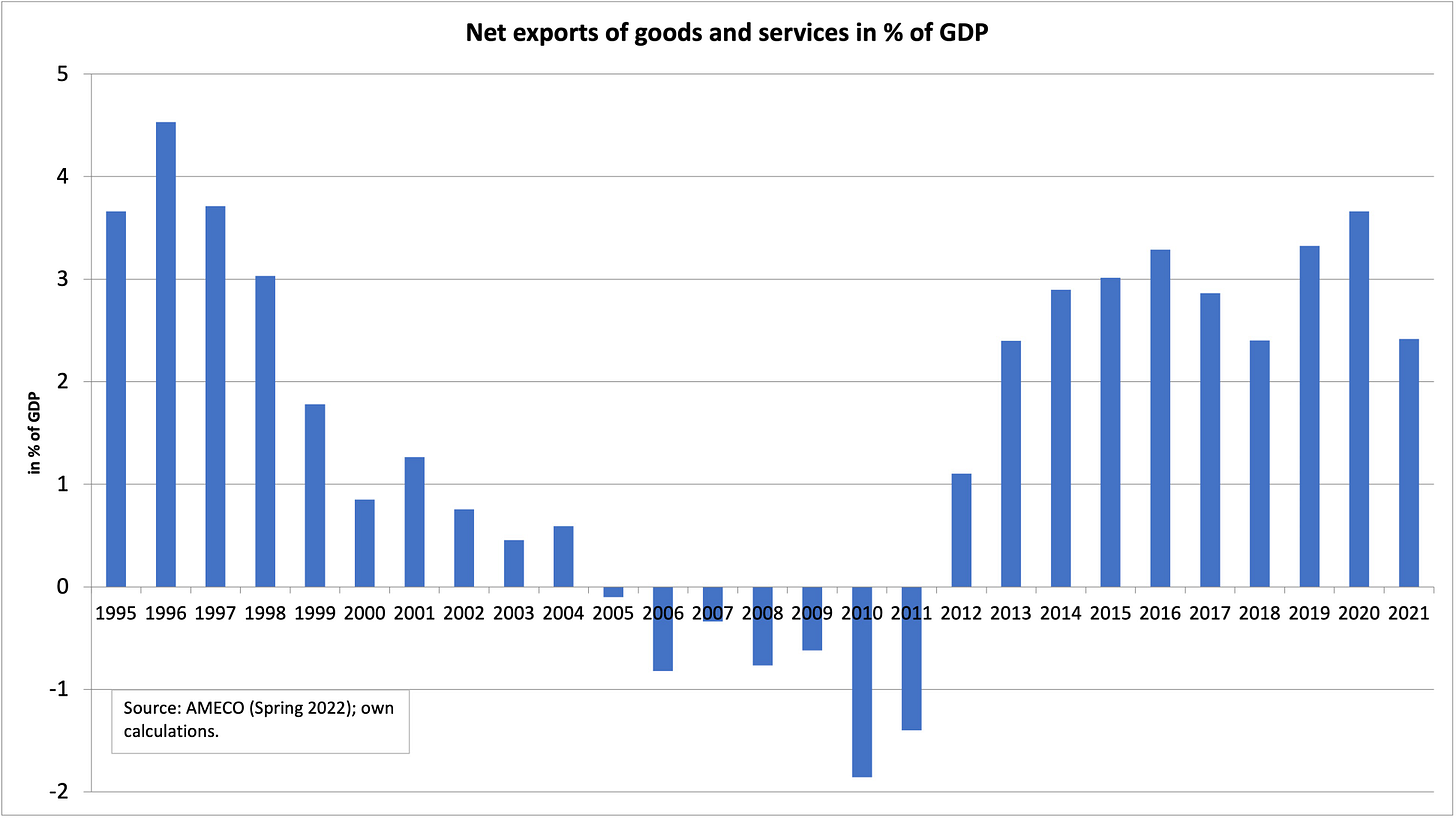

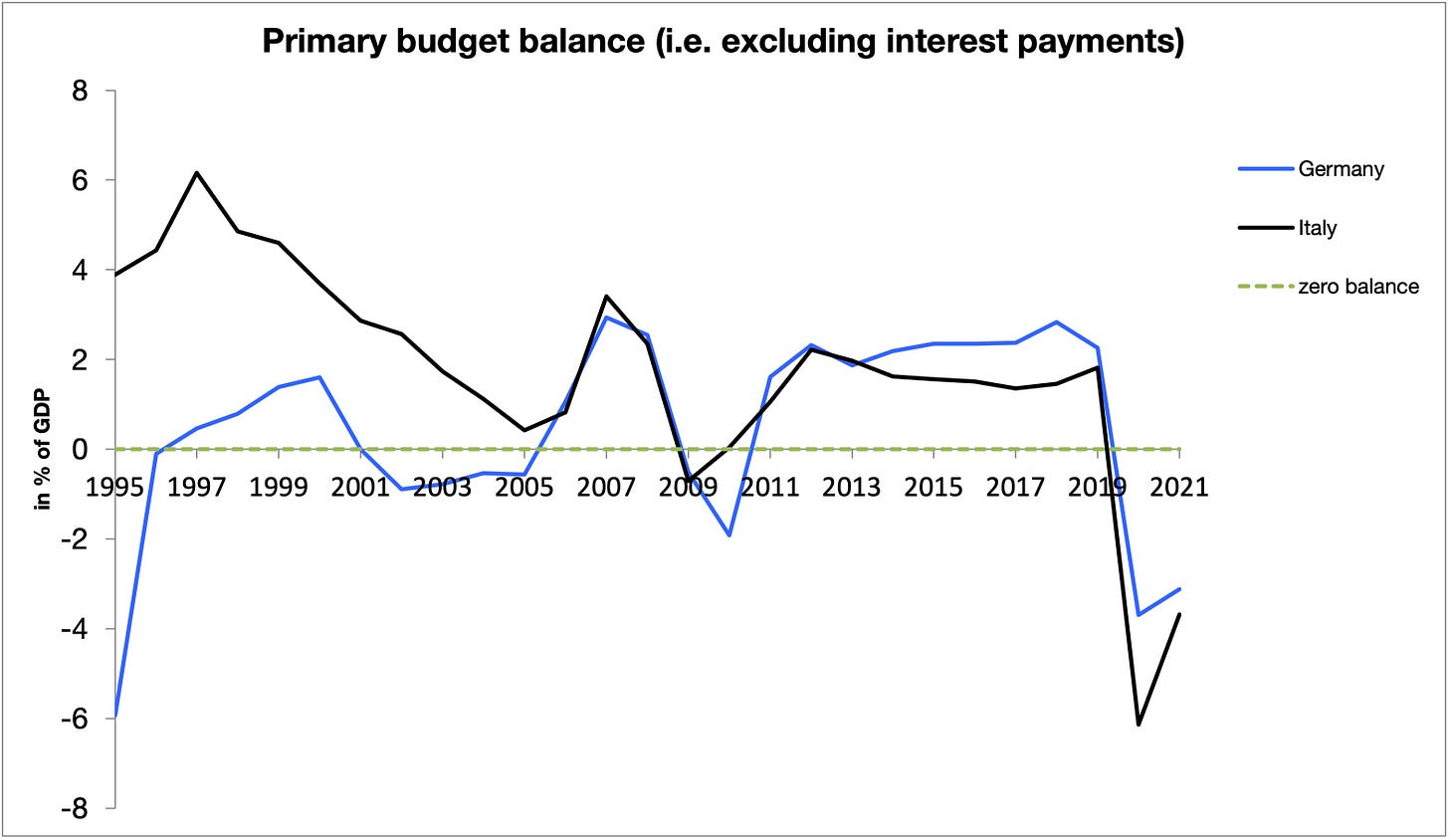

High public debt is primarily a legacy from the 1970s and 1980s and the impact of deep economic crises over the past two decades. Furthermore, the mistakes that were made 40 years ago took place in an environment of rising interest rates. Since then, the Italian state has been carrying a heavy interest-rate backpack. If we exclude the burden of interest rates, however, the Italian state consistently ran budget surpluses from 1992 up to the Covid-19 crisis.

Source: AMECO.

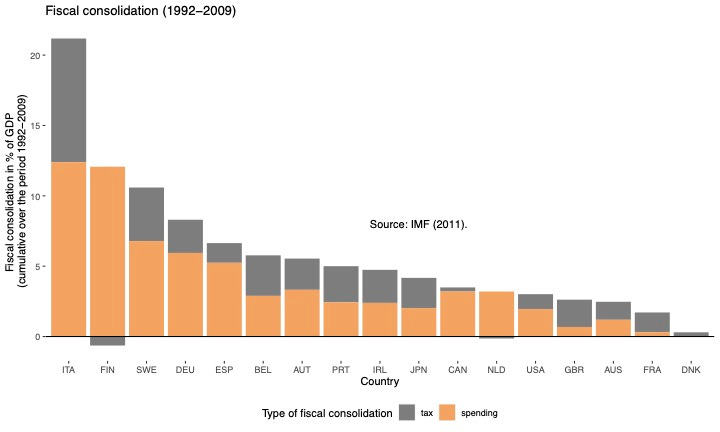

Even Germany, Austria and the Netherlands recorded a comparable ‘primary’ budget surplus less frequently than Italy. The Italian state has not been as ‘profligate’ as is often claimed: it has consistently collected more in taxes than it has spent. IMF data show that Italy implemented the most severe fiscal consolidation packages of all advanced economies between 1992 and 2009, especially when it comes to spending cuts.

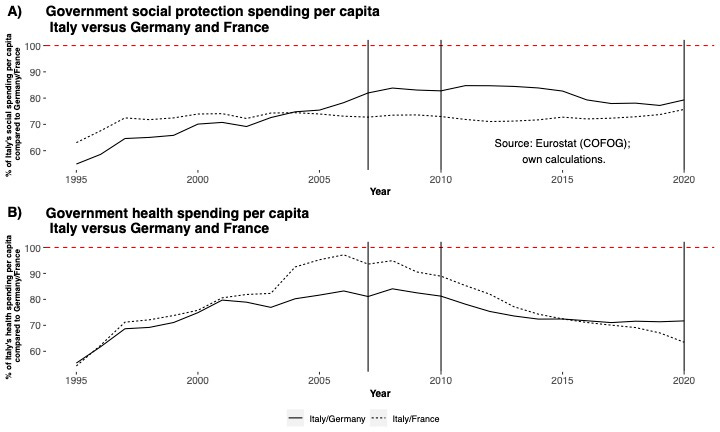

Per capita spending of the government for social and health is much lower in Italy than in Germany or France. But the interest burden—high due to legacy debt—has repeatedly pushed the overall budget balance of the Italian state into negative territory. Fiscal consolidation has contributed to weaker domestic demand for goods and services, which has led to lower economic growth.

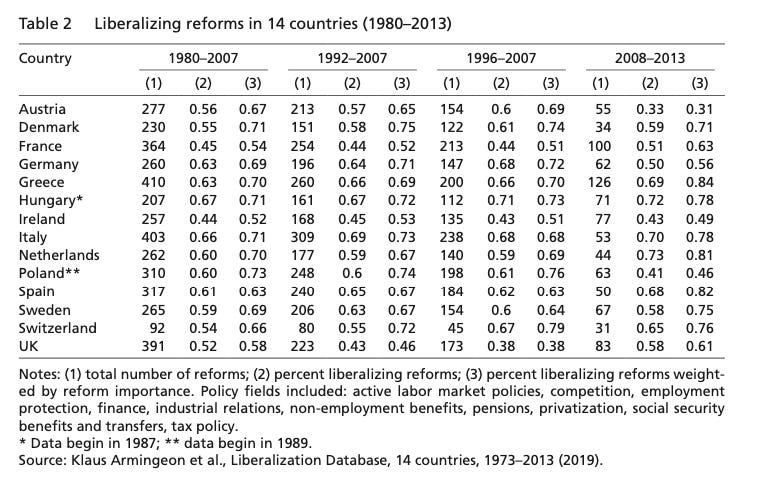

Italy has carried out many market-liberal reforms

Italy’s “reform efforts” have been significant; Italy is actually a top performer in liberalising reforms over the past decades compared with other advanced economies. Overall, Italy has adhered much more closely to the EU's reform policy rulebook than Germany or France.

Source: Baccaro and D’Antoni (2020).

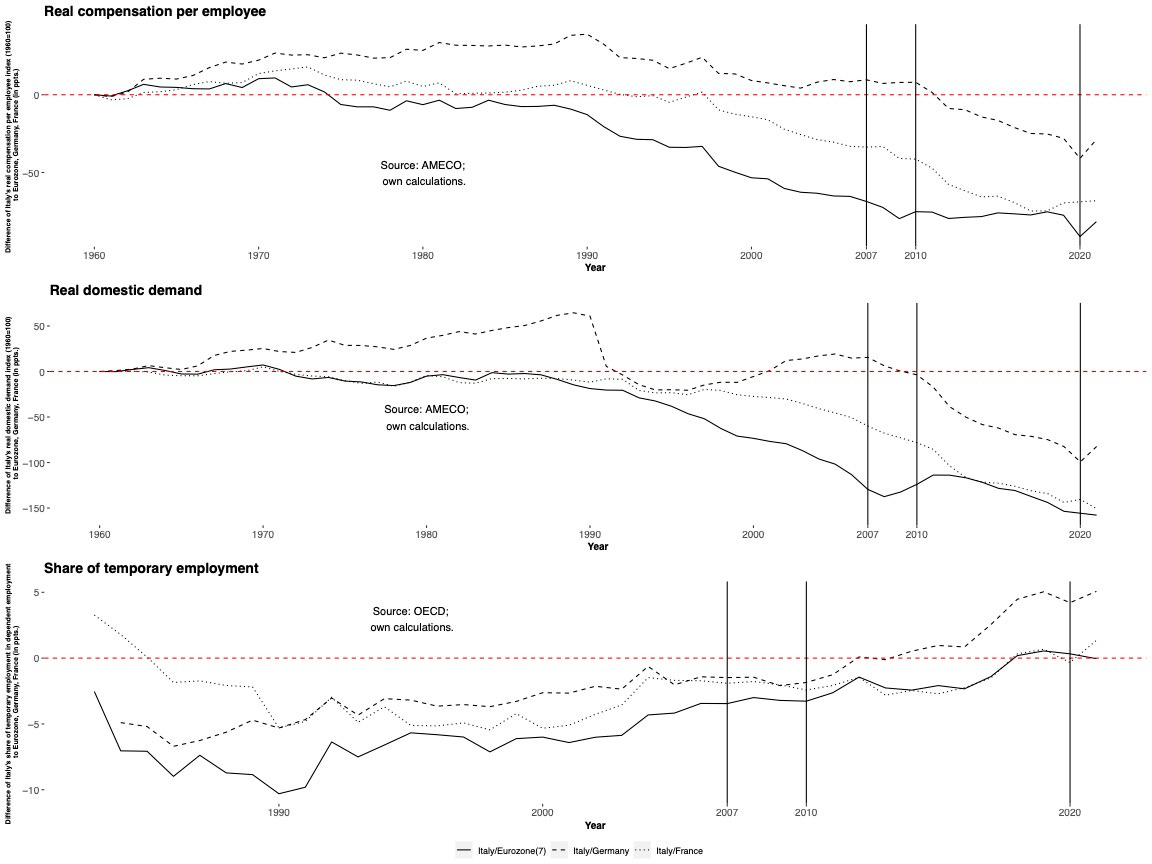

A flexibilisation of the labour market since the 1990s brought a sharp increase in fixed-term contracts, a pushback against trade unions and a decline in real wages compared to Germany and France. These measures not only reduced inflation in the 1990s. Cheap labour has increased the labour-intensity of production, thereby reducing the incentives for labour-saving investment by companies. Private investment, however, is key to rising productivity and is particularly crucial in high-tech sectors. Productivity growth is in turn the basis for growth and rising incomes. Market-liberal labour market reforms have thus arguably done more harm than good to Italy's productivity growth.

Italy remains the second-largest industrial location in the EU

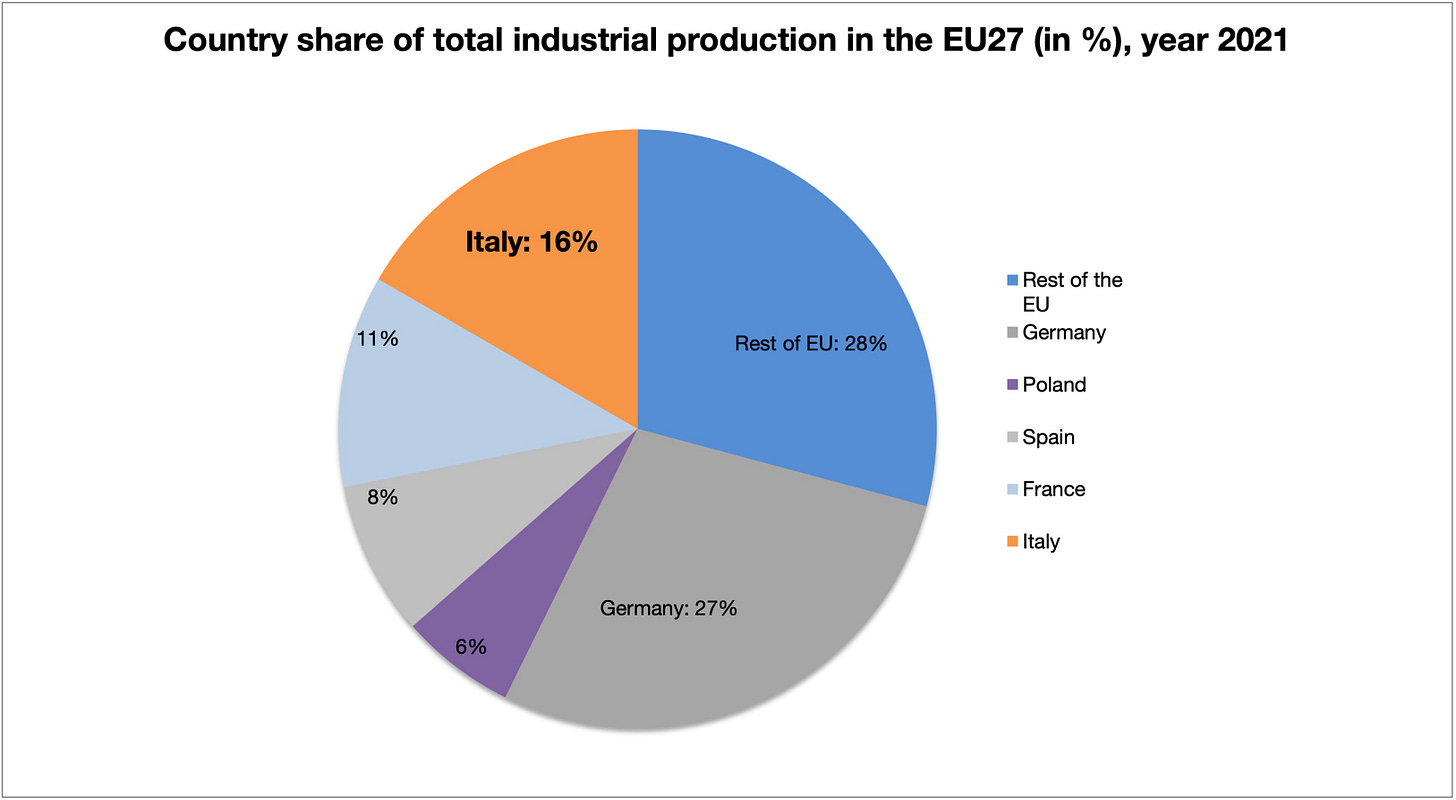

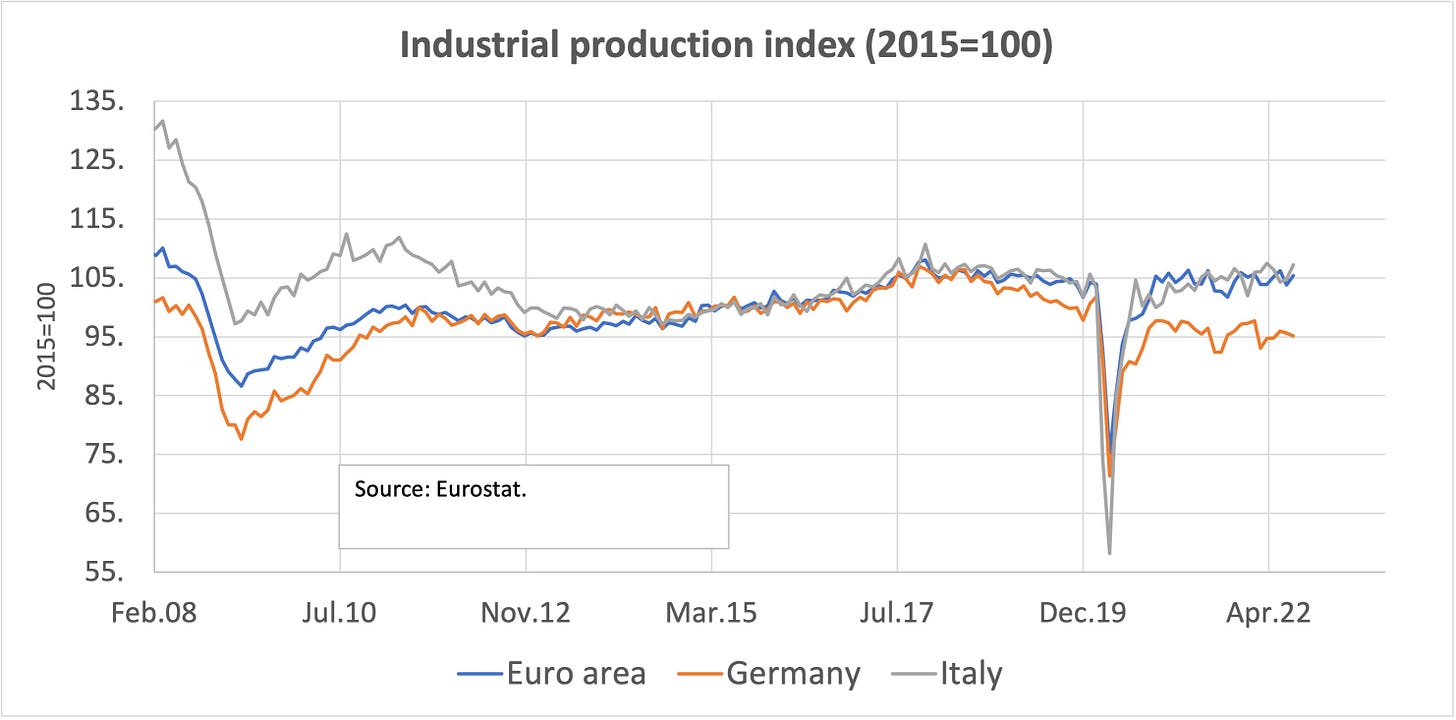

It continues to surprise people in Germany, Austria and beyond that, despite weak productivity growth and problems with price competitiveness within the euro area, Italy has important economic strengths. Italy is still the second most important industrial location in the EU (which would be true even if the United Kingdom were still part of the EU), mainly due to the economic structure in the north of the country.

Source: Eurostat.

The country has the second highest share in EU industrial production after Germany; it has exported significantly more industrial goods than it has imported, including during the Covid-19 crisis. By far the most important export sector is mechanical engineering, followed by vehicle construction and pharmaceutical products. These sectors rank under "medium-high-tech" to "high-tech" industries in the OECD’s classification. Over the last eight years, Italy’s industrial production has outperformed Germany.

Challenging myths to improve economic policy

Similar to other European countries, Italy certainly has its own significant structural problems. These problems include the North-South polarisation of the country, weak productivity growth and dysfunctional elements of the political system. As the EU’s third-largest economy with tight trade links, other EU member countries certainly also have a keen interest in seeing positive economic developments in Italy. But instead of asking how European policy mistakes during past crises – such as pushing Italy deeper into fiscal austerity during the Euro Crisis – may have contributed to the long rise of the right-wing and a major decline in voter turnout, most European observers simply reacted to the Italian election results by expressing that they are “very concerned” about Italy, which should double down on doing its “homework”.

There is little critical thinking about how EU policy-makers could support Italian politicians in coming up with a credible strategy on opening up a positive development perspective for Italy beyond sticking to the Covid-19 recovery fund. A first step would require us to get rid of the wrong standard narrative about how Italy ended up in long-term economic decline. This must involve an analytical consideration of how domestic Italian factors have interacted with the policy constraints imposed by European integration and globalisation to accelerate Italy’s decline since the 1990s.

If austerity policies and market-liberal reforms have failed to move the country forward over the past decades, then the obvious thing to do is to develop a coherent long-run investment strategy and give Italy's industry a boost by launching a modern and green industrial policy strategy. Macro policy and labour market policy need to consider that efforts to push down labour costs have had negative effects on wages and domestic demand, exacerbating the problems of labour productivity growth. European policymakers need to support a proper coordination of wage, industrial and fiscal policy by rethinking the rules of the game, e.g. with regard to reforming the EU’s fiscal rules and industrial policy strategies.